Here's an open letter to the new King of England.

Dear King Charles:

You may have noticed a September letter addressed to you from Texan Eric Williams who is demanding the return to America of a quilt in Bath’s American Museum in Britain. Mr. Williams has decided that his great-great grandmother Mirriam R. Williams, a woman once enslaved at the Mimosa Plantation in east Texas, “was a part of the group that made the chalice quilt,” which has been in the collection of the American Museum since 1983. Mirriam’s grave in the Mimosa Hall cemetery indicates she was about 19 when slavery ended. She died in 1872 at the age of 25.

See her grave marker here: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/200137934/mirriam-r-williams

The "Chalice Quilt" was donated by “Mrs. W. Webster Downer,” Marguerite Linam Downer who also donated a World War II memorial quilt made for her husband by his grandmother Mary Earl Webster Downer (1878-1956.) Mary Downer lived at Mimosa Plantation near Leigh, Texas after the Civil War. A 1983 publication listed the recent acquisition:

"Mrs W. Webster Downer has donated a quilt made by slaves on the Mimosa Hall Plantation, Texas. Legend has it that when the Bishop came once a year from New Orleans to confirm, baptize and marry his scattered flock, and stayed with different families on the many cotton plantations in the area, it was the custom to make a new quilt for his use on each visit." America in Britain, Friends of the American Museum in Britain, 1983

“Legend may have it” but we go too far in accepting legend as historical fact. Eric Williams “believes the quilt was stolen from its intended destination,” and he’s indignant. In late September, he sent a letter to King Charles III and the museum asking the quilt be returned so it can be placed in the Martin Luther King Jr. Museum.

He noted that the quilt “is a piece of cultural heritage that was used to hide secret codes for runaway enslaved people traveling on the Underground Railroad. That whole entire quilt was designed as a roadmap for runaway slaves utilizing the Underground Railroad. That's a culturally significant heritage piece to all people of color," he said.

Mr. Williams is referring to what is known as the Quilt Code, a widely discredited story that quilts during the days of slavery held secret meaning in their array of patterns like the Drunkard’s Path and the Sailboat (again patterns not seen before 1865)

Fergus M. Bordewich, author of Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America wrote a critique of the Quilt Code in “History’s Tangled Threads” in the New York Times February 2, 2007.

“So it’s not surprising that the intriguing (if only recently invented) tale of escape maps encoded in antebellum quilts — enshrined in a metastasizing library of children’s books and teachers’ lesson plans and perhaps even in a Central Park memorial to Frederick Douglass — should also seize the popular imagination. But faked history serves no one, especially when it buries important truths that have been hidden far too long. The ‘freedom quilt’ myth is just the newest acquisition in a congeries of bogus, often bizarre, legends attached to the Underground Railroad.... The notion of maps hidden in quilts surfaced in the 1980s — in a children’s book, according to a quilting historian, Leigh Fellner, who has shown that many of the patterns supposed to contain ‘coded’ directions for fugitives date from the 20th century.”

Eric Williams: "The museum has made money off of a quilt they did not manufacture for many years, and there's a need for reparations and returning the quilt.“

I don’t quite understand his indignation here---the Museum has not sold reproductions or even pictures of the quilt. All museums with material culture use objects "they did not manufacture" as their stock in trade, their wealth.

The red and white quilt is part of their collection, perhaps not a popular geographical choice for a permanent home, but one the donor and the curator thought appropriate at the time. It is also important to remember that the American Museum does not show British material culture but American objects.

What Mr. Williams believes and the historical facts diverge widely. First of all the quilt is not reliably dated to before 1900. (It would have to have been made before 1865 to have been stitched by enslaved people.) It is likely a 20th-century quilt.

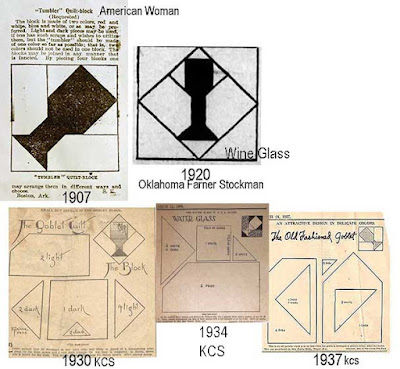

Comparative dating includes the quilting design, the patchwork goblet pattern and the fashion for Turkey red and white quilts, all of which date to "after 1880." The distinctive pattern was published four times between 1907 and 1937 in periodicals that appealed to women.

If the quilt had meaning to the maker (we cannot mind-read the anonymous

maker's intent) it would more likely have been as a temperance statement focusing

on a goblet of water (advocated as an alternative to alcohol) by the popular

Women's Christian Temperance Union here after 1870 or so.

The Mimosa Hall quilt's donor Marguerite Downer, who’d lived in England for a while, was communicating about quilts from her husband's family. Louisiana born, she never lived in Texas and seems to have told a family story with a few time distortions. Curator Kate Hebert has recently re-examined the correspondence between the Museum and the Downers and found that the American donors referred to an "Episcopal" bishop visiting Texas but museum labels changed the reference to the English “Anglican.”

Marguerite's son Charles Downer wrote a letter to the Museum in 1997 that included this statement, presumably from his father, who might have been more familiar with the family story than wife Marguerite:

"This quilt was made by one of the slaves on my great-great-great-grandfather’s plantation in Texas, Mimosa Hall. Some 80 years later, my grandmother, Mrs Mary Earle Webster Downer (the great-granddaughter of John Webster) made a 'victory' quilt for me during the second world war… My grandmother was raised at Mimosa Hall and learned to quilt under the same roof as her great grandfather’s slaves who made the chalice quilt.’

The last sentence is a good clue to the confusion. "My grandmother was raised at Mimosa Hall and learned to quilt under the same roof as her great grandfather’s slaves who made the chalice quilt." His grandmother Mary Earle Webster was born in 1878. The women who taught her to quilt were NOT slaves, but former slaves--if indeed they were her quitmaking teachers." If Mary Webster learned to quilt as a child this would have been in the latter part of the 1880s. The problem is the confusion between the terms "slaves" and "former slaves." We have thousands of quilts made after 1865 by "former slaves."

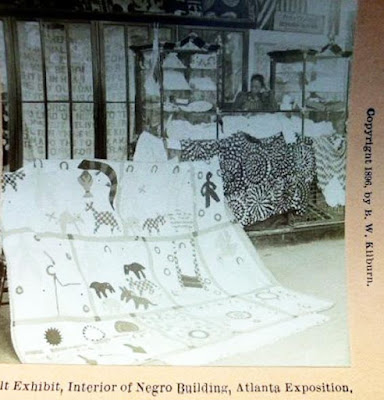

While quilts by "former slaves" are certainly worth studying and preserving they do not give us much evidence of life in slavery; they were not stolen or were they coded escape maps.

The idea of the visiting bishop is an intriguing side-light to the quilt's story. Episcopal clergy did travel to visit the faithful. One large branch of the African-Methodist-Episcopal church in the U.S. has a tradition of visiting bishops. Perhaps a bishop visited Leigh, Texas to baptize the new babies and marry the flock in the 1900-1930 era. He might have been quite pleased to sleep under a quilt that spoke not of Anglican chalices but Temperance values.

In conclusion, Dear King, I would advise you to tell Mr. Williams that there is no evidence the quilt was "stolen," slave made, part of any quilt code or that it belongs in the United States. And if you need any more advice about quilts and other issues, I'm glad to help.

Read a post I wrote a few years ago about this quilt here:

https://civilwarquilts.blogspot.com/2018/02/slave-made-quilt-unlikely.html

See a feature on Eric Williams's indignation here:

Sincerely

Barbara Brackman, Self-appointed quilt historian and Know-It-All

PS: I got so worked up about the whole thing I am going to talk MORE about the issue in tomorrow's November 9th premiere of our Know-It- Alls show (Episode #20). The link to buy tickets today & tomorrow:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/the-know-it-alls-episode-20-serendipity-tickets-463567622237

.jpg)

I hope King Charles reads your blog!

ReplyDeleteLove your letter to King Charles!

ReplyDeletePersonally I think you should send a copy of this and your other research and reasoning why Mr Williams is wrong to him and the museum, suggest the museum correct their information (or at least flag current information as possibly inaccurate) and tell them to put whatever it brings at auction to good use.

I'd suggest sending it to Mr Williams as well, but he would probably not appreciate having the errors in his story pointed out.

just to clarify - send this to King Charles and the museum.

DeleteI have been working with the museum. They are interested in correcting the errors made 30 years ago.

DeleteAwesome news!

DeleteGood work Barbara! I have also seen the "code quilt" being used in fictional stories and stated as fact. Thanks for the temperance connection.

ReplyDelete