Library of Congress

Mary Woodburn Greeley (1788-1855)

probably taken in the early 1850s, from a scratched

daguerreotype produced by Mathew Brady's studio

This woman was remembered fondly by son Hod,

who left a record of her life giving us some insight

into woman's work in early 19th-century New England.

Horace's birthplace (the one & a half story cottage) in Amherst,

New Hampshire still stands.

According to her son, Mary the young mother (she eventually had seven children) added to the family income with spinning and weaving work. His autobiography tells us that she manufactured cotton, wool and linen goods at home to sell to local textile enterprises.

Mary was put out of her home work by industrialization. Mechanized textile mills that developed in

Greeley's youth in the teens could produce cloth cheaper and more efficiently with a less-skilled labor force. There was no longer a market for hand production at home.

The account of Mary's textile work in the teens is a small glimpse of pre-industrial New England and women's work.

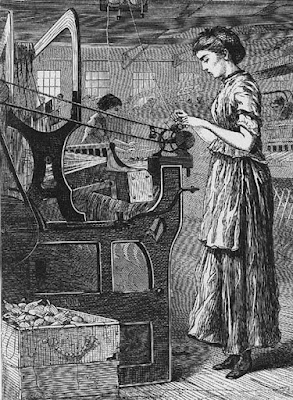

New York Public Library Collection

Working much like this hand weaver 100 years later.

Greeley's youth in the teens could produce cloth cheaper and more efficiently with a less-skilled labor force. There was no longer a market for hand production at home.

Unmarried young women with no child care needs

found work in the new mills, here winding bobbins for the machines.

The Greeleys lost the farm and moved to western Vermont when he was about ten. Horace recalled:

“We had been farmers of the poorer class in New Hampshire; we took rank with the day-laborers in Vermont.”

In an 1810 report to Congress Albert Gallatin estimated, "Every second [New Hampshire] house, at least has a loom for weaving linen, cotton, and coarse wool cloths, which is almost wholly done by women." Elizabeth Hitz also calculates half of New Hampshire's families had a loom in the home, based on the 1810 census. (In Maryland one family in twelve had a loom according to her book A Technical and Business Revolution: American Woolens to 1832.) We often assume the spinning and weaving went to clothe families but many of those women, like Mary Greeley were professional textile producers.

We know much more about the difficult transition from home production to industry in England where many of the skilled home workers seem to have been male, perhaps an important difference in handling that transition.

The legendary and imaginary leader of the Luddites

Ned Ludd dressed as a woman

In England weavers conducted violent protests after being put out of work by mechanized looms. We hear of the Luddites who wrecked machinery in raids beginning the year of Horace's birth in 1811. "Machine breaking" was made a capital crime and protesters were hung. Legend has it the male raiders often dressed like women. In the United States where women appear to have been the home weavers there was no Luddite protest. Families like the Greeleys who lost an important part of their income followed Horace's later advice to "Go West."

Horace's New Hampshire memories also include references to a social event his mother attended. Rather than bringing their plain or fancy sewing the "matrons" brought spinning wheels small enough to carry under their arms.

No comments:

Post a Comment