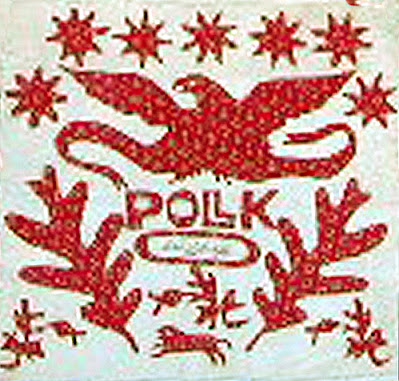

The Polk's Fancy pattern we've been looking at in the recent two posts is certainly evidence that women in the mid-19th-century used quilt patterns to express political preferences. If one looks in the literature for information about politics and quilts one is sure to come upon a cliché of this order:

The Cliché:

Women denied the right to vote were indifferent and unwelcome in political discussion. The implication is that they coded their rudimentary political interests into decorative needlework like patchwork. There is some truth in the statement: 1) Women in the 19th-century generally could not vote. 2) There are many patterns like Polk's Fancy with political names.National Museum of American History

Block from Susan Underwood's 1844 album

If we want to look at women's lives we have to dismiss that oversimplification.

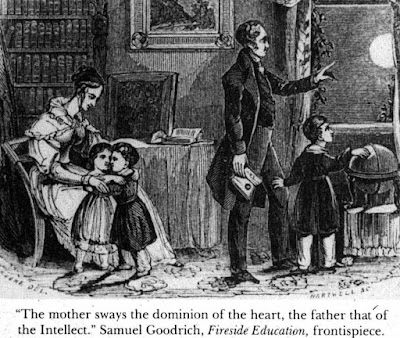

When Cuesta Benberry & Carol Crabb wrote that sentence in 1993 they were influenced by perceived wisdom about female participation outside the sphere of the home. The historical construct of "Separate Spheres" dominated women's history for several decades in the late 20th century.

The idea that woman conformed to the social dictates preached by pastors, nagged upon by husbands and mothers and that Godey's repeated ad nauseum was. like so much conventional wisdom about culture, an idea that diminishes the individuality of the people the historians are trying to study.

Godey's Lady's Book 1851

A few quilt patterns from the 1840s & '50s when designs began to multiply in infinite variety were a product of the political culture of the era. Partisan designs were not the coded opinions of a few barrier breakers. Women participated much more in political activities whether they could vote or not.

Accommodations for ladies attending an 1844 Whig Convention.

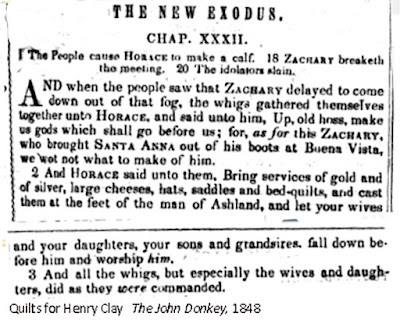

The two dominant political parties, Whigs and Democrats, made a concerted effort to engage women in politics. And women responded with among other tributes, bed-quilts.

Bring large cheeses and bed-quilts and cast them at the feet of Henry Clay, 1848 satire about Whig Henry Clay (the man of Ashland), Democratic opponent Zachary Taylor (hero of the Mexican War battle Buena Vista) and we can assume New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley.

Were the Whig women imitating the Democrats? Looking

back we find a lot more Whig Clay quilts than Democrat Polk, but here's

evidence that both sides encouraged needlework tributes.

More satire, a pun on counter-pane.

The Locos were a nickname for a Democrat faction.

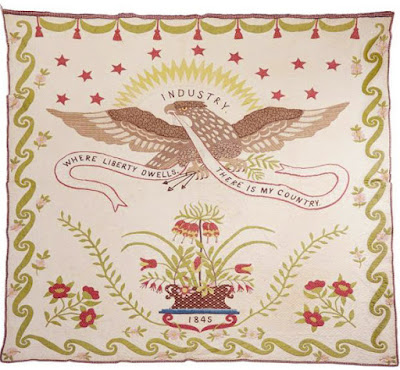

M.A. Young won a prize for her Whig banner quilt in Utah in 1857.

Freeman's Auction, quilt dated 1845

Attributed to Hannah Ryan Smith (1795-1866) of Massachusetts & New York

Clay ran several times on a platform of Whig

protection with tariffs for American industry.

Democrats, especially Southern Democrats,

strongly opposed that protection.

Quilt signed Phelps, 1853.

Sotheby Auction

Sotheby's assumes it was made in Phelps, Ontario County, New York

Elizabeth K. Varon on women in Virginia: Whigs "sought to capture the presidency of William Henry Harrison partly by energizing its voter base with meetings and hoopla....Whig womanhood embodied the notion that women would could---and should---make vital contributions to party politics."

Raccoon on the Samuel Williams album (1846-1847)

at the Baltimore Museum of Art

Jeff Bridgman Antiques

The Coon was a compliment, the party's symbol.

Maryland Historical Society

Note the Raccoon in the tree next to the log cabin, both symbols of the 1840 Whig candidate William Henry Harrison who won that first election full of knick-knacks, slogans, imagery and hoopla.

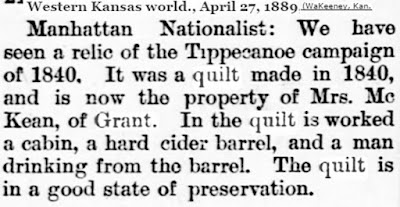

And where is Mrs. McKean's quilt today?

Album 1847

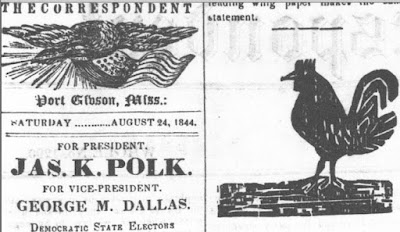

The rooster the Democrat's mascot.

Polk's Fancy

Block that used to be in political collector Julie Powell's collection.

No comments:

Post a Comment