Remarkable quilt on display at the Smithsonian's National Museum

of American History for a few more weeks.

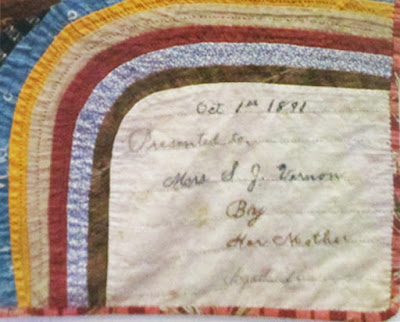

"Oct 1st 1891

Presented to

Mrs. S.J. Vernon

By

Her Mother

Aged 76 years"

The exhibit is in a case on the main floor next to the Batmobile.

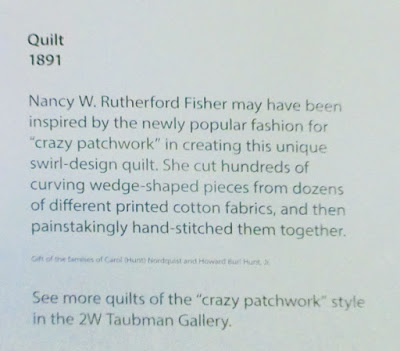

The family who recently donated the quilt believe the maker, mother of Sarah Jane Fisher Vernon, was Nancy Rutherford Fisher, born in Bath County, Kentucky in 1815; died in Clover Bottom, Franklin County, Missouri 1901, ten years after the date on the quilt. The Rutherfords were one of many Kentucky immigrants to Missouri, immigrating as a family in the 1820s when Nancy was a girl; they lived in St. Louis and in Franklin County, west of St. Louis and close to the Missouri River, the great Western highway.

Here's Nancy's grave:

"S.J. Vernon

Born Feb 16, 1844

Died

Sept 2 1906"

Nancy married Bavel Fisher (1808-1882) in 1833 and had 8 children. (Did anyone else get a quilt?) Daughter Sarah Jane moved to Hunt County, Texas after marrying James Mulkey Vernon in 1873, where she died five years after her mother gave her the quilt.

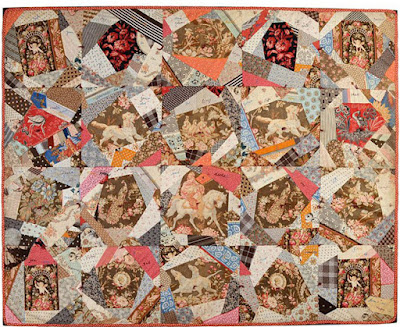

It's just about impossible to get an all-over photo of it but I

took some details when I was in Washington in October.

Difficult to photograph as a whole, but you get the idea.

It's one big swirl of hundreds of long irregular pieces with curved edges.

See her post here:

I pirated a few from the internet too.

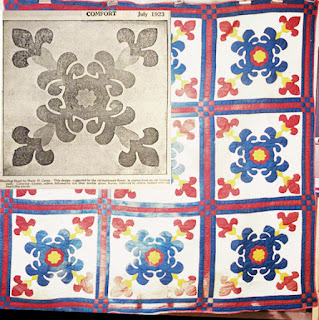

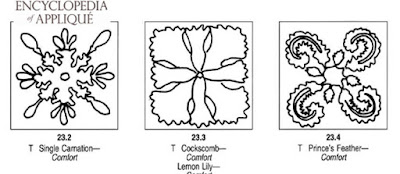

The pattern was quite the thing about 1900.

From the Quilt Index

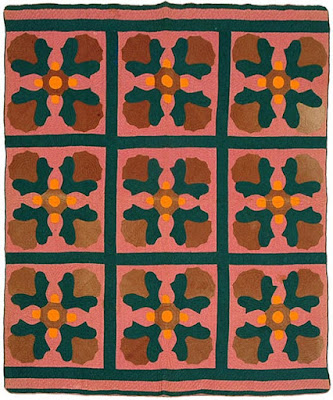

Martha Spark pointed out a more conventional version done block-by-block in the collection of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum.

Similar fabrics, same time.

Online auction

A block-by-block pattern relatively common; the medallion idea---this

may be the only example.

Nancy "cut hundreds of curving wedge-shaped pieces from dozens

of different printed cotton fabrics...."

Thinking about cutting scraps reminded me of something I read in a Comfort magazine from the 1920s. A contributor with a pattern for a scrappy quilt explained:

"Patchwork is not the cutting up of whole cloth into bits for the sake of sewing it together again, as has been said by someone, but rather the utilizing of goods which is already cut up. A really attractive quilt results from the ingenious ways in which these scraps are used."

The central swirl

In another issue of Comfort from about the same time Mary Gilbert of Iowa explained:

"There is always an accumulation of new bits of percales, ginghams and other sorts of wash goods where the clothing for the family is still made at home, and the quantity of those scraps is, of course, usually regulated by the size of the family and the care which is taken of them."

Now, one cannot imagine that a family would have

this many strange-shaped scraps left over from

garment making (no matter what the size of the family)

Louise thought about the source for the fabrics and did a little follow-up.

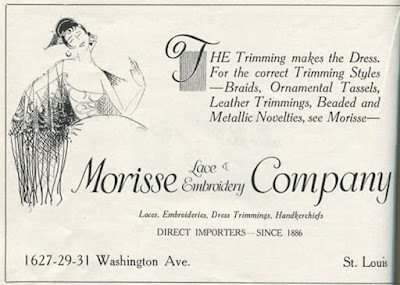

"The quilt had its start in Missouri, then traveled down to Texas to the home of Sarah Jane (Fisher) Vernon in 1891. It is quite possible that the fabrics used to make the quilt were obtained from the dry goods store Nancy’s nephew worked at in St. Louis, Missouri. He was a merchant for the wholesale house Morisse Lace and Embroidery Company. From Texas, the quilt made its way to California, and now finally to its permanent home in Washington, DC."

1924 ad for Morrise Lace & Embroidery Company --- since 1886.

Family in the fabric business is often behind a masterpiece quilt. But I would think it more likely that Nancy Fisher's fabric source was factory cutaways, scraps from a clothing factory. St. Louis was not home to any cotton-producing mills but there were undoubtedly ready-to-wear clothing factories there in the 1890s.

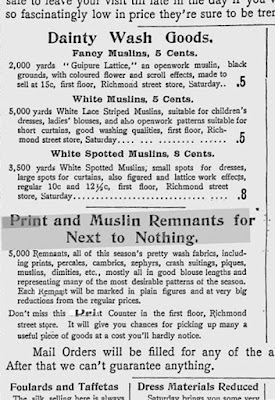

Toronto Daily Mail, 1900

Factory cutaways were also commonly retailed by stores, through the mail and by clothing factories. One would guess that Northern sources would sell the prints, percales and cretonnes produced

in nearby textile mills.

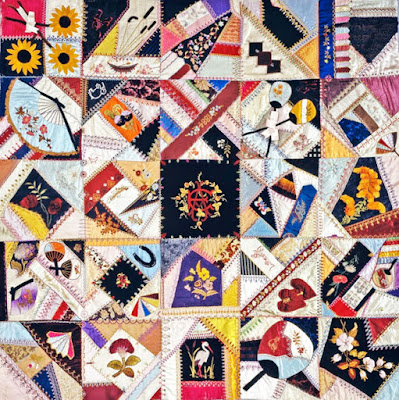

From Stella Rubin's inventory.

A New England style scrap quilt featuring pictorial cretonnes.

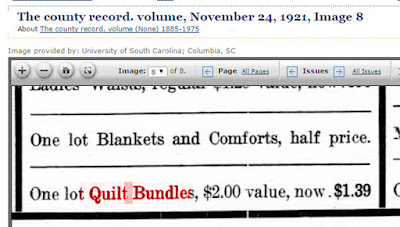

1921

Southern stores, like this one advertising in South Carolina, would likely

be selling the solid color cottons and yarn-dyed woven patterns we

see so much in Southern quilts.

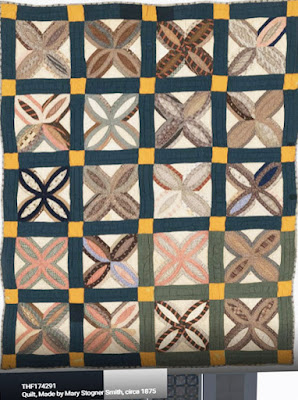

Mary Stogner Smith, Georgia

Collection of the Henry Ford Museum

1915 Manning, Clarendon County, South Carolina