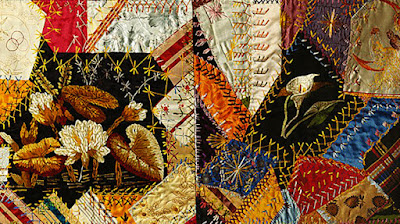

Crazy quilts must have been fun to make. They're certainly fun

to look at, especially the earlier, more lavishly detailed examples from

the early 1880s until about 1900.

The later quilts are simpler in their imagery and variety, more

reliant on hand drawn imagery than commercial sources.

National Museum of American History

Smithsonian Collection

There do seem to be contrasting skill levels in some of the decoration---an intriguing circumstance, which has prompted me to look closely at the silk versions.

It's interesting that most of these commercial sources did not advertise their wares for crazy quilts---but of course the quilters appropriated any visual imagery they came across.

Bird & daisies skillfully done.

Moon......

It looks like this maker (not greatly talented at the linear stitches) made

use of ribbons sold for dress and hair trim.

Other incorporated ribbons were woven

pictorial Stevengraphs, this one a Washington

tribute with a little added embellishment.

Benjamin Harrison ribbon, perhaps a Stevengraph.

Harrison was president 1889-1893.

President Grover Cleveland served twice during the height of the

crazy fashion: 1885-1889 & 1893-1897.

Printed silks were less expensive than woven Stevengraphs. Political and commemorative

ribbons were popular additions.

Illinois State Museum Collection

(They called them badges rather than ribbons.)

"Family Cares" a scrap of printed silk from???

New Jersey project & the Quilt Index

Pieced & appliqued patchwork was added, often fans---another silk fashion of the times.

National Museum of American History

Text, such as monograms drawn from the commercial sources of the day.

Florals done in three dimensions with folded ribbon and plushwork

National Museum of American History

Lydia Finnell---plushwork lily & owl

Painted florals

Painted monogram on an Iowa quilt recorded

by the Massachusetts project & the Quilt Index

Odd scraps from other needlework projects....

But the major decorative imagery was embroidery using

filled and outline techniques.

National Museum of American History

Usually filled with a satin stitch.

1886 How-To on the Satin Stitch

1899 advice on what was also called the Kensington outline stitch,

named for the London needlework school that revived embroidery

in the late 19th century.

Barry in outline stitch. Read more about Barry here:

Advertisement for a book with "Kate Greenaway designs for Doyleys, etc."

These nostalgic children were quite the fashion and many crazy quilts

include them.

Sewing kit of leather with painted Colonial child---a "Kate Greenaway figure"

National Museum of American History

And then there are the scraps that appear to have been commercially

produced, purchased and attached.

Lancaster Historical Society

More about that tomorrow.