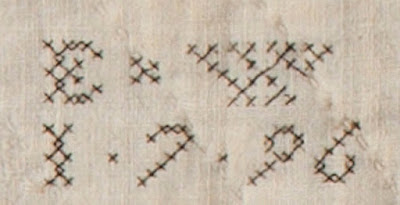

International Quilt Study Center & Museum #2008.040.0083

We’ve looked at an array of high-contrast dark and light ground quilts from about 1785 to

1820, among the earliest of American styles. Comparing this undated Pincushion or Orange Peel quilt from the Dillow Collection to dated quilts gives us an estimated date.

Rachel Mackey, Chester County, Pennsylvania, date-inscribed 1787

I recently re-read book The Growth of the British Cotton Trade 1780-1815 by Michael M. Edwards looking for answers. The basic answer seems to be that the cottons that dictated patchwork style were unavailable before that date. Cottons from India and China had been printed for centuries and imported to Europe as luxury goods, but American patchwork style and the British printing industry are closely linked.

Elizabeth Webster (1777-1840), Harford County, Maryland,

Date inscribed 1796. MESDA Collection.

Read more about this quilt here:

http://mesda.org/item/collections/quilt/1641/

Why no cotton quilts here before 1780? Because cotton fabric was not available. We can look at trade, technology and taste for reasons. Trade is always important as textiles have long been a basis of international economies. Revolution in North America meant no English imports until after the peace in 1783, but even had ships been sailing from England to New England there would not have been much British cotton to carry.

The technology for the cotton prints in Elizabeth's quilt developed during her lifetime, particularly in

the last thirty years of the 18th century. Cotton is difficult to spin by hand or with early mechanized machinery. Eighteenth-century cotton yarns were better for weft than warp, which is why so much mixed fabric of linen and cottons (fustian) was produced.

the last thirty years of the 18th century. Cotton is difficult to spin by hand or with early mechanized machinery. Eighteenth-century cotton yarns were better for weft than warp, which is why so much mixed fabric of linen and cottons (fustian) was produced.

Medallion quilt, collection of Connor Prairie Museum.

There were bottlenecks at every step of cotton production from field to cleaning and carding, spinning yarns and weaving cloth.

And the raw cotton was hard to obtain; it’s a fussy plant with soil and climate determining quality.

Cradle Quilt, Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Robbins family, Lexington, Massachusetts

Cylinder printing in the 19th century

Technological changes resulted in plentiful goods resulting in changing taste. Women's gowns became simpler, suitable for lighter cotton rather than silk, wool and linen. Cheaper fabric for the gown meant more money for accessories, such as cashmere shawls and fur tippets. Cotton was easily laundered resulting in an emphasis on personal hygiene, the Beau Brummell look of starched, clean garments. And inexpensive fabrics meant a more egalitarian look across the classes.

By 1811 a British "Lady of Distinction" was called to condemn the evil of “the present leveling modes. A tradesman’s wife is now as sumptuously arrayed as a countess, and the waiting maid as gaily as her lady.”

Sheraton-style chair with a chintz seat

International Quilt Study Center & Museum #2007.031.0007

Mary Campbell Ghormley Collection

International Quilt Study Center & Museum #2008.040.0131

Byron and Sara Rhodes Dillow Collection

So I can give up looking for American cotton patchwork before the last quarter of the 18th century and change my mind about pieces like the two below.

Connecticut quilt with embroidery from the mid 18th century

and patchwork from the late century.

From a Cora Ginsburg catalog

Once I would have looked at the patchwork and the embroidery as being from the same time frame and considered a mid-18th-century date, but this is a case of someone incorporating an older embroidered piece into a later bedcover.

Ditto below.

From the White Family of Massachusetts. Collection of the Smithsonian

And that's the end of the posts on high-contrast quilts and dark-ground chintzes---I'm impressed with the style's popularity and how many survivors are in public collections. Just imagine how many did not survive. It must have been a real craze.

You covered that topic very well. It has been really interesting to me, thank you :D

ReplyDeleteKerry, I of course think it's fascinating so I'm glad you were interested.

ReplyDeleteLove the browns. I've been thinking of making an orange peel quilt but in blue -- of course!

ReplyDeleteI wonder from this if you can extrapolate that lindsey woolsey was made for the same reason?

ReplyDelete