1797, Hannah John. Documented by the Maine Project.

One of my quilt history goals last year was to develop an accessible internet file of quilts with dates inscribed on them. I created Pinterest pages for each year or decade from 1775 to 1860. Date-inscribed quilts give us insight into how style, fabric and techniques came in and out of fashion.

Here's a link to the oldest quilts from 1775 to 1800:

This year my goal was to analyze those images between 1775 & 1860 and draw some conclusions. I've looked at a lot of chintz appliques.

Quilt dated 1826 by Sarah Harris Gilmer

Documented in the North Carolina Project

Analysis is always more complex than sorting and saving and I have not clarified many conclusions that were not obvious when I began. For example, red and green quilts date to the 1840s.

1842, Elizabeth Shank, Rogerville, Ohio

Collection: Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum

I'm still working on it.

As with any data set there are outliers---quilts that are the earliest or the latest example of a style or technique.

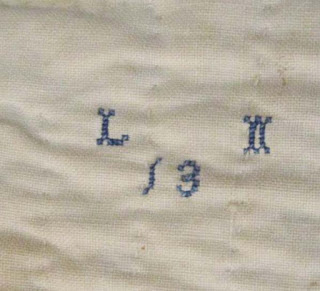

Typical household linen marking stitch on the

reverse of Elizabeth Nace's nine patch quilt

Dated 1786, Elizabeth Bowman Nace (ca. 1740-1815)

Hanover, Pennsylvania. Lancaster Historical Society

Among the earliest American quilts, one of perhaps five dated before 1790.

Looking at some of the outliers in the data I wonder if there is a big flaw in my reliance on date-inscribed pieces because the date on the quilt might not be when the patchwork was done. It might be the date on a pre-existing backing or supporting fabric. In this case, an old linen sheet cut up and saved in the backing.

Marking sheets with cross stitch embroidery and a number was considered good housekeeping. This marking "L N 13" on the reverse of a nine patch strip quilt indicates the backing was an old sheet recycled.

From online dealer gb-best

Housekeepers often dated their linens, their sheets and blankets. Sometimes these pieces were transformed into another piece of bedding, a patchwork quilt. A linen sheet dated 1786 might be used to back a cotton quilt in 1810.

1809, Quilt by Elizabeth Stouffer Garrett, (1791-1877)

Baltimore Museum of Art

The quilt is dated 1809 in cross stitch on the back with the initials E.S. and the number 7.

If made in 1809 this quilt is a significantly early example of a tree of life chintz quilt. (See Sarah Gilmer Harris's 1826 quilt above.) It's been puzzling me ever since I first saw it in William Dunton's 1945 book. Could the date be on a re-purposed backing?

On the other hand the Baltimore Museum of Art has other Garrett family quilts with the same kind of inscription on the backing, indicating the Garretts marked their quilts like their sheets.

See a blog post on the Garrett quilts:

Those of us who see early quilts only in photographs are not aware that many cut-out chintz applique pieces feature chintz prints stitched to a machine woven blanket, as in this detail from a Skinner auction. We tend to think of the backing as plain weave cotton purchased just for the patchwork but that is not the case in many early 19th century quilts in the U.S. and the U.K.

Center of a frame quilt with a date of 1824 directly above the large

oval in the panel. It's probably British.

"Ann Price

1824"

The inscription indicates this is one of the earliest quilts in the files Merikay Waldvogel and I are keeping of this particular panel #1. But that date seems to have been on the base fabric, a re-used blanket perhaps.This piece also has some mid-20th century repairs---definitely a time span quilt.

Collection of Gawthorpe Textile Collection

"E I 1812"

Another British quilt, this one dated 1812 and initialed E I, skews our data on panel quilts with an early date. Without the date we'd guess 1820s. But is the date of the supporting fabric?

Did someone applique panels, hexagons and flowers atop an old linen sheet?

The central embroidery with the framing lappets is thought to be an 18th-century piece saved in the later bedcover---but how late?

Most of this post is speculation but it does give one a different perspective

on early quilts and the sources of the materials.

On quilts where the date appears on the front, is that a more suggestive date for the patchwork or appliqué?

ReplyDeleteMy thought is, if I were re-purposing a sheet for a quilt top, I probably wouldn’t make a mark like those you describe part of the design. I’d more likely cover it with appliqué, or not include that section in a parch.

But my motivation and that of a woman 100 or 200 years ago, of course, may well be different.

I’m a little unclear on these marks. We’re they needed for commercial laundries or communal clothes lines? Or to inventory sheets for rotation and tracking how long they lasted? Or ...?

Great post!

That is SO interesting, and does give a different perspective. I don't suppose, unless you have a body of work from the same woman or family, that it's possible to know if they numbered quilts like sheets, or if they reused sheets, or exactly what happened. I enjoyed thinking about this puzzle, so thank you for the post.

ReplyDeleteYou can see from estate inventories that, in the late 18th & early 19th century, bedclothes, including sheets, were among the most valuable furnishings in the home. The sheets were monogrammed and numbered to identify them and prevent theft. Often there were servants, guests and many other people in the household, it was important to keep track of all the linens at all times. I've never heard of "commercial washing companies" in this era although in cities at least there were plenty of women who "took in" washing to support themselves. I'm not sure that the people who marked their linens sent them out, but the mistress of these households likely did not personally do the laundry. Washing and ironing was a horrendous task before washing machines that involved a great deal of heavy lifting of wet cloth and hauling many buckets of water often heated for the wash and rinses.

ReplyDeleteI too greatly appreciate the history research and thinking that goes into this blog. Always good questions that we will not likely get answers to, but will keep us thinking.

ReplyDelete