The oldest quilt in America?

The fragment of the quilt in question is 16-1/2" tall,

showing what was probably a floral medallion center framed

by a vine and next a field of clamshell quilting.

We've made some educated guesses about this quilt fragment supposedly made in 1682 by Sarah Kemble Knight, estimating its actual date as a century or more later (1750-1840) and speculating that Massachusetts teacher Adeline Morse brought it to Greensboro, Alabama in the 1830s, where somehow it was transferred to neighbors the Croom/Hobson family.

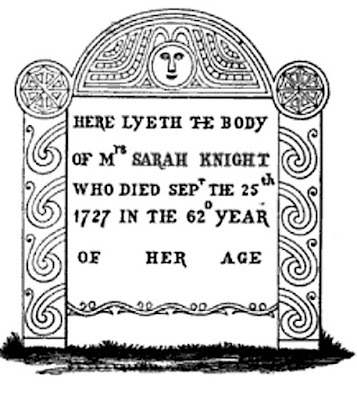

Why is it connected to Sarah Kemble Knight? An attached note is said to have written by Sarah before she died in 1727.

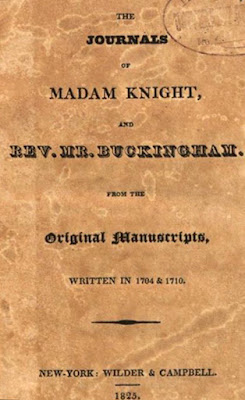

If the note is indeed in her hand there are many researchers into Colonial diaries who would be thrilled to see it. People have been discussing Sarah Kemble Knight's travel journal since 1825 when Connecticut-born author Theodore Dwight published it in book form. It is a book that Greensboro teacher Adeline Morse might have been familiar with from her New England girlhood.

Theodore Dwight II (1796-1866) at 32 in 1828, a few years

after publishing his Sarah Kemble Knight journal.

Portrait by John Trumbull

New York Historical Society

Scholars with far more credentials than I have presented evidence for and against the authenticity of the Sarah Kemble Knight diary. New England textile historian Lynne Z. Bassett refers us to an essay by Peter Benes, published in the Proceedings of the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, "In Our Own Words: New England Diaries, 1600 to the Present" (Boston University Press, 2009). Lynne tells us, "it reveals serious doubt as to the authenticity of the diary that made Madame Knight famous (a doubt that has overshadowed the diary since the 1840s)."

The journal tells the story of two 1704 journeys by a 38-year-old Boston widow who traveled without escort to settle estates in New Haven, Connecticut and Manhattan, New York. The Journal of Madam Knight has been enjoyed over the past two hundred years for the liveliness of its narrative, the unusual nature of a lone journey by an intrepid female and her saucy nature, rather ahead of her time for a Colonial dame. Someone actually called her the Dorothy Parker of the early 18th century.

http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/becomingamer/growth/text1/connecticutknight.pdf A university curriculum recommends it:

We could go into detail about Theodore Dwight's publishing career but his most relevant book is another personal narrative with which he's associated, published in the periodical The Protestant Vindicator in 1835. The Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery of Montreal was then published as a salacious anti-Catholic book, supposedly a memoir of rape, murdered babies, etc. that was a sensational best seller, igniting the Nativism politics of the next few decades. Dwight is considered by many as the ghostwriter to whom alleged nun Maria Monk told her stories or most likely, the author who fabricated the tale out of whole cloth shall we say (and made a fortune.)

Sarah Kemble Knight (1665-1727)

There is no doubt there was a woman named Sarah Kemble Knight who left much evidence of her existence in Massachusetts and Connecticut. But did she leave a journal?

From an 1865 edition of the diary, republished many times.

Theodore Dwight's first edition included two diaries. Read excerpts from Madam Knight's journal here in a PDF:

http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/becomingamer/growth/text1/connecticutknight.pdf A university curriculum recommends it:

"This journal is one of the most teachable colonial documents at the undergraduate level. Students respond positively to Knight's humorous portrait of herself and her surroundings. Through this document--and others--a teacher can counterbalance the still all-too-common stereotype of Puritans as dour, somber, unsmiling, and morbidly pious."

We could go into detail about Theodore Dwight's publishing career but his most relevant book is another personal narrative with which he's associated, published in the periodical The Protestant Vindicator in 1835. The Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery of Montreal was then published as a salacious anti-Catholic book, supposedly a memoir of rape, murdered babies, etc. that was a sensational best seller, igniting the Nativism politics of the next few decades. Dwight is considered by many as the ghostwriter to whom alleged nun Maria Monk told her stories or most likely, the author who fabricated the tale out of whole cloth shall we say (and made a fortune.)

Maria Monk's confessions about sin in Catholic convents is still in

circulation, believed by gullible haters.

But as Dwight wrote to Charles Deane in an 1846 letter, there really was no manuscript to show.

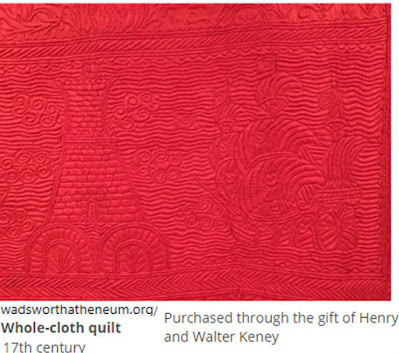

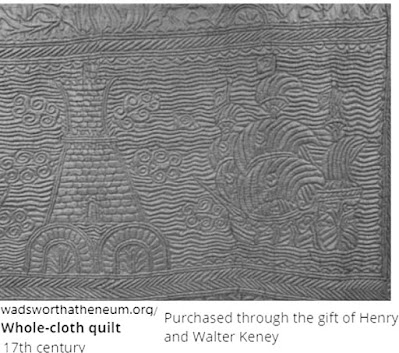

Quilts did exist in 1682. Museums own well-preserved examples of silk, whole cloth quilts from the 17th century and earlier with a similar look.But the imagery and the sources are completely different; these very early bedcovers were commercial products for world trade, luxury goods sent to the West from China and India. The earlier quilts also are stuffed and corded, techniques rarely seen in New England's wool and silk quilts.

Collection

of the Wadsworth Anthenaeum

Lynne Z. Bassett has examined another quilt attributed to Sarah Kemble Knight now in New London, Connecticut. As it is a printed monochrome toile giving more clues to date Lynne assures us: "It was indisputably not made by Madame Knight, as it was made of a later 18th-century toile.

"Unfortunately I have but two or three leaves of Madam Knight's original manuscript remaining; for, after preserving it some years as a precious piece of antiquity, an Irish servant, one unlucky morning used the greater part of it to kindle the fire....Painful it is to add that....a number of letters of the same Madam Knight...was committed to the flames a few years ago in New London. Traces of them were found...."

A little Photoshopping to show the quilted imagery

and the filler quilting in parallel lines behind the florals.

Scholars of Colonial history can and will discuss the journal's authenticity---I haven't much to add. But I do know quilts and I have to say there is no way the Alabama quilt fragment had anything to do with either Sarah Kemble Knight or the 17th century. Quilts did exist in 1682. Museums own well-preserved examples of silk, whole cloth quilts from the 17th century and earlier with a similar look.

Silk quilted bedcovering, ca. 1600

Collection of Colonial Williamsburg

A black & white photo shows the imagery, ships and seas depicted with

corded lines of quilting

A late-18th century fabric, a monochrome toile, printing

techniques invented long after Madam Knight's death.

Tomorrow's Post: Why do the

stories linger?

Ah but it was a fun tale. It's unfortunate that these tales are taken as "truth". Thanks for your part in this.

ReplyDeleteLoving the history.

ReplyDelete