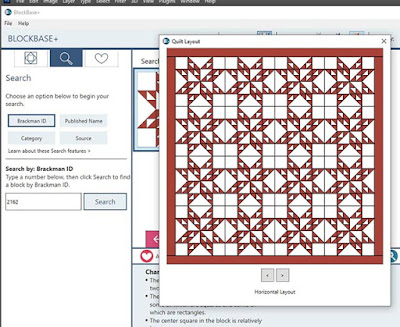

1881 Sarah Henshaw Putnam (1800-1894)

General Artemas Ward House Museum at Harvard

Inscribed: "This quilt was made by Mrs. Sarah H. Putnam of Shrewsbury Mass January 1881 for her nieces Elizabeth Ward and Harriet Ward."

Over the past two days we've been looking at quilts with the date 1881 inscribed:

A recent detail photo shows us that Sarah's quilt is

not in the same condition now that it was in the above overall picture.

"I remember the days of old."

Looking at cotton quilts from 1881 tells a little about fabric style and innovations in dyes, colors and color combinations. Sarah Henshaw Putnam may have been 81 and remembered "the days of old" when she stitched this quilt for her nieces but she knew what a younger generation might like. None of that old-fashioned madder brown. She chose new-style bronzey greenish-browns, a fresh look in prints.

That fabric style also appealed to the women who made this album.

The papers with their names on them are still stitched to the blocks, some of them dated 1881.

The new shades of brown also appealed to friends of Jennie Watkins

whose 1881 quilt is in the Benton County Oregon Historical Society.

Another album quilt, this one from Maine.

The new browns offered novel color combinations within

the prints, a combination of brown, tan, red, pink & blue with white

that must have looked quite innovative.

Mrs Noble seems to have been quite up-to-date in

her color choices. The border is probably a cretonne stripe,

a large-scale furnishing print often done in the bronzey

brown combination palette.

This photo of a quilt dated 1881 in the lower left is too vague to show us the actual prints but it does look like the browns are greener than the madder browns so popular a few years earlier. There seems to have been a real shift in taste, which is always based on what fabric is available.

Ad from Montgomery Ward's 1881 catalog listing their cotton prints from the New England mills like Sprague and Cocheco. The prices---4 cents to 25 cents--- are cheap when compared to the $2 silks we saw yesterday. Imported Turkey reds were the most expensive at 25 cents but domestic Turkey reds were less than half that. See also #10 plain color red prints (dyed in the cloth) for 7 cents.

(I'd splurge on the 25 cent reds---you know what happens to the 7 cent reds.)

No information on a quilt dated 1881 in the quilting.

The ad tells us a lot about the types of fabric one could buy in 1881 and also how available the New England prints were to anyone who could receive the U.S. mail (and had to cash to send.)

Quilt top dated 1881

Charleston South Carolina Museum

From Maine to South Carolina.

"Jacob Bender / Oct. 3, 1881 Martha Bender / Oct. 3, 1881"

And West Virginia where Anna Martha Bender (1864-1938) whose name is on this pattern we'd call Drunkard's Path may have bought the 9 and a half cent indigo blues ("blue, white figures, stripes or dots") by mail or at her local drygoods store.

See another of Martha's quilts here:

The divide between regional styles North and South in the 1880s probably reflects the changing retail situation in that decade as railroad shipping, central warehouses, mail order and new Southern mills matured as economic factors.

The Kronheimers who ran the dry goods store in Oxford, North Carolina up by the Virginia state line probably complained a lot about competition from mail order sources. They just couldn't stock the variety that Montgomery Ward's could. You can see the Kronheimers advertised a limited amount of fabric in this 1881 ad:

- Bleached and unbleached cotton (we assume plain white utilitarian yardage produced locally.)

- Beautiful spring Prints..... (from New England?)

- Cassimeres, Kentucky Jeans &c, (probably wool/cotton fabrics that also came from local North Carolina mills.)

Why would anyone shop locally?

There are, of course, many reasons. One: The operative word in mail order is money. The customer had to send some kind of legal tender to shop by mail. But back home the Kronheimers surely understood the local tobacco economy and agriculture's annual cycle in which credit was extended until the fall crop came in and yearly accounts were settled. Shoppers who lived in this economic system were essentially forced to shop locally where their credit was good. Thus, the Kronheimers prospered.

Kronheimer home in the 1880s

The Kronheimers' local competitor W.R. Beasley ran a general store

advertising a similar non-cash exchange for groceries, hardware & clothes.

"We will take all kinds of country produce in exchange for goods.

Wheat and corn...for which the highest prices in cash or barter will be paid."

Oxford in the 1940s

Granville County farmers took their corn to Beasley's and traded crop for the goods he had in stock. The farmer's wife, the dry-goods purchaser, undoubtedly looked forward to her fall shopping but it was limited to what local stores carried.

Granville County chickens in 1937

Photo by Dorothea Lange, Library of Congress

She might have traded her own crops of eggs and butter for fabric too.

Oxford's A. Crews & Brothers, merchants, advertised a barter system in the 1870s.

"We will take in exchange for goods the following substantials: Gold, Silver, Greenback, Old castings, rags, beeswax, peas, corn, cotton, fodder, oats, wheat, meal, flour, dried fruit. In fact anything that can be turned in to money. We take this method of returning thanks to the public generally for their past favors and hope to merit a continuance of the same."

Rosa Oakley, her husband Titus and children James, Mary Lois and the

baby Jean in 1939 preparing the tobacco crop in their bedroom.

Photo by Marion Post Wolcott, Library of Congress

WPA Photographers made several trips into Granville County.

Life had changed little in 60 years.

Samuel L. Howe's dry goods store in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

Collection of Historic New England

Undoubtedly quiltmakers in Massachusetts and Rhode Island also bartered with local merchants, trading farm goods for factory goods but the "fabric department" in those New England stores would also have been local, cottons from the nearby mills that specialized in complex prints.

New England style on the left/Southern style on the right

The difference between what was available in a New England store and its counterpart in the upland South may explain growing differences in regional quilt style after 1880. One could in theory buy up-to-date sophisticated, colorfast prints anywhere in the U.S. but differences in what local mills manufactured and what local store owners stocked was regional. Customers locked into an agricultural economy had to shop local even if the Southern mills were producing inferior, cheap yardage, which might have been suitable for baby clothes and aprons but far too fugitive for heirloom quilts.

Socializing at Mrs. N.L. Clement's store in Granville County, 1940

Photo by Jack Delano, Library of Congress.

1881 Collection of Marjorie Childress

Northern mills with many more decades of experience produced a

more reliable product.

Sallie A. Bachman signed and dated her quilt of

green calicoes, probably from a New England mill.

Marjorie found it in New York.

Undated quilt found in Tennessee

Undeterred by second-rate fabrics Southern quilters

spent many hours on precision piecing.

So what have we learned about quilt style from a close look at quilts inscribed with the date?

It may just be coincidence that none of the 1881 quilts feature them but people no longer seem interested in the madder red-brown prints on the left (quilt dated 1872.) The different shade of brown with pinks as accents instead of oranges was what was fashionable (or available.) No other fabric style differences pop out in looking at the 34 quilts dated 1881 and that may be why there are so few quilt---fabric just wasn't that interesting or innovative (yet.)

The most important observations may be the differences in economics dictating retail purchasing North and South, which seem to have generated new and distinct styles that only increased in the decade following.

And there are some absences---no crazy quilts and no utilitarian wool quilts yet. Hard to know what else is missing. Certainly not any great creativity in patchwork pattern--probably because periodicals and catalogs still had relatively limited illustration capabilities.

But here are a couple of quirky quilts dated 1881 that add little to the discussion

From a Sotheby's auction.

From the New Jersey project & the Quilt Index.

The last of the quilts dated 1881:

Too small a photo to see the fabrics...looks like a classic pattern that could have been made anywhere. The Louisiana Project tells us it's signed Edna, 1881. Edna seems to have been a traditionalist.