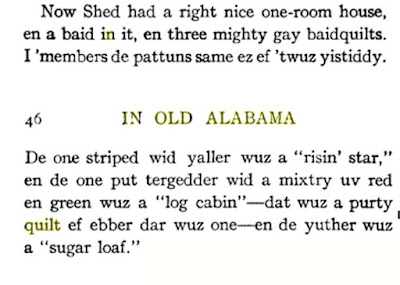

The last 4 posts have examined the tale of America's oldest quilt, featured in the book Alabama Quilts where it is dated 1682. Facts do not substantiate that claim.

Links to the previous four posts:

https://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2021/01/a-1682-quilt-in-alabama-1-oldest.html

https://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2021/01/a-1682-quilt-in-alabama-2-new-england.html

https://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2021/01/a-1682-quilt-in-alabama-3-break-in.html

https://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2021/01/a-1682-quilt-in-alabama-4-who-was-sarah.html

Reprint

about 1850

3) Then there is slander, such as the

anti-religious propaganda of the Maria Monk diaries, attributed to Theodore

Dwight, thought to be the author of the forged diary of Sarah Kemble Knight.

4) And, unfortunately, some people have psychotic episodes believing voices are dictating stories to them.

6) Often it is the message that matters. Some people desire an idea to be true so firmly that they see nothing wrong in a little lying.

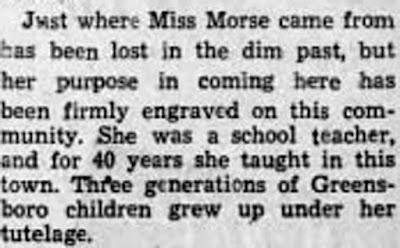

Did Alabama teacher Adeline Morse embellish a Massachusetts family quilt with a lengthier pedigree---just as she may have shortened her own when telling the 1870 census taker that she'd been born in 1820.

The complex tale of the 1682 quilt, America's "oldest quilt," its link to Sarah Kemble Knight and the Journal of Madam Knight probably weaves threads of various motivations. Slander would have little part in it and nobody seems to have heard voices so the strongest motivation for the persistence of the Sarah Kemble Knight myth might be the message this tale tells us.

Sarah Anne Hobson (1874-1953)

Anne and sister Margaret were keepers of

family heirlooms like the quilt fragment & family stories

We could find a parallel in the

image of the Southern plantation historic home.

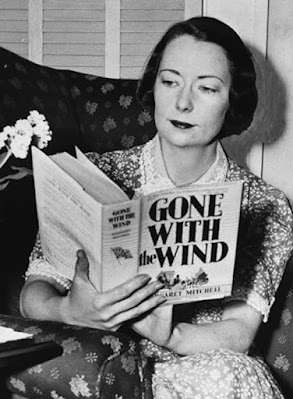

Karen L Cox in Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created notes that in the Gone With the Wind novel Margaret Mitchell described a more typical and more modest house but set decorators created a new fiction. Mitchell "feared that Hollywood might add columns 'on the smokehouse, too.' "

Margaret Mitchell (1900-1949)

Mitchell: "Southerners could write the truth about the ante-bellum South [but] everyone would go on believing in the Hollywood version."

I'm afraid the "1682" quilt relates more to the Hollywood version than to the accurate textile history version.

And that's a wrap on quilts from 1682.

Although you could read Karen L. Cox's Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created