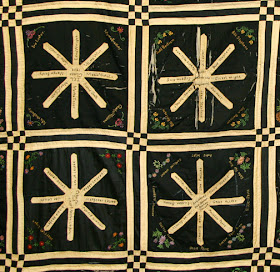

Detail from an embroidered quilt, ca 1900, in the collection

of the Jewish Museum

My cousin sent an April 12, 2014 article from the Jewish Daily Forward called "Why Jews Suffer from a Quilt Complex?" Author Jenna Weissman Joselit discussed why her Jewish "home and ... parents’ home and ... grandparents’ homes were entirely quilt-free."

"East European Jews and their descendants, as I've just discovered, had little truck with quilting. Feather bedding was one thing; patchwork quilts quite another."The article:

http://forward.com/articles/196183/why-jews-suffer-from-a-quilt-complex/#ixzz2ymyvYwz4

This is true in my personal experience too. My Jewish grandmother's house (and my Irish-Catholic grandmother's house---both in New York City) were entirely quilt-free.

My Jewish grandmother loved handwork,

knitting full outfits (skirt, cardigan and shell) and

crocheting doilies similar to this by the dozens.

- One: Contemporary quilters working after 1960

- Two: Historical quilts made before 1960.

A layered patchwork textile with layers held together by quilting or tying.

Contemporary quilters working after 1960

Rosh Hashana by Linda Frost, 2010

This quilt traveled in a 2012-13 Smith-Kramer exhibit

America Celebrates! Quilts of Joy and Remembrance.

Historical quilts made before 1960

The Reiter/Freidman family Baltimore Album quilt

1848-1850, Baltimore

Collection of the American Folk Art Museum

One of three similar Baltimore album quilts attributed to Baltimore's Jewish community about 1850.

Read more here:

http://www.folkartmuseum.org/?p=folk&t=images&id=4268

Quilt photographed during the Kansas Quilt Project

We looked at the quiltmaker's religion. About 59 percent of the quilts were identified as being made by a quiltmaker with a known religious affiliation. The number: about 7,700 quilts. The highest percentage (22.5%) was made by Methodists followed by people identified as generic Christians, then Roman Catholics, Baptists, Presbyterians and Lutherans---not surprising as these specific denominations ranked highest among Kansans in general in the 1980s.

Fundraising quilt made by members of the Sunday School,

First

Methodist Episcopal Church, Topeka, Kansas, 1883.

Collection of the Kansas State Historical Society.

Church members paid a dime to have their names included.

The contrast between Roman Catholics and Methodists was interesting, however. Catholics made up the highest percentage of Kansans (34.6%) at the time, with Methodists at 26.9%. Yet Catholics did not make quilts in proportion to their numbers either in 1886 or 1986. Catholics made 7% of our total; Methodists over three times as many.

I did the accounting and was surprised to find that of all those quilts only six were made by Jews: Six quilts made by 1-1/2 quilt makers identifying themselves as Jewish. I know it was 1-1/2 because I was the half and a friend was the whole. We both began after 1960.

The Kansas Quilt Project also asked about quiltmakers' ethnic origins and found over 8,000 identifications. British heritage was first with 41% reporting that background, German ethnicity was a close second at 38% and then the numbers dropped to 13% for Scandinavian, 5% for French and 1% for Czech. Ethnicity such as Italian, Mexican, Amish and Jewish were insignificant at less than 1% each.

Fundraising quilt made by women of the

First Baptist Church, Jamestown, Tennessee

1937-1939. From the Quilt Index.

Community members paid a dime for each embroidered name

raising $22.10. The quilt then sold for $10.00. The $32.10 bought chairs

for Sunday School.

My theory at the time of writing the book on the findings of the Kansas Quilt Project:

"Protestant church activities, such as Sunday School quilts and Ladies' Aid Society quilting groups traditionally were a strong influence on quilting."

Lititz, Pennsylvania, 1942

Photo by Marjory Collins. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The caption: "The Moravian sewing circle quilts for anyone at one cent a yard of thread and donates the money to the church."The Moravians in the photo, like many Protestant women's church groups, raised money for church improvements and maintenance by taking in quilting, an activity still carried out in church basements. Women also raised money by charging for signatures, and by raffling (if such gambling was allowed) and auctioning quilts.

Quilt auctions raise significant funds for the

Mennonite Relief Services.

Based on data from the Kansas Quilt Project and personal observation I would have to agree with Jenna Weissman Joselit that quiltmaking was not a popular activity among Jewish women in the past.

There are, of course, exceptions to the rule. Bertha Stenge was one of the most prominent quiltmakers of the 1940's and '50s, winning national prizes with her work.

Bertha Sheramsky Stenge (1891-1957)

Bertha Stenge, The Quilt Show

Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago

See more of Stenge's quilts here at the Art Institute

And read a biography here:

http://www.museum.state.il.us/ismdepts/art/collections/daisy/biography.html

Berger/Miller quilt

Another of the 1850 Jewish Baltimore Albums

from the collection of Jane Katcher

Bertha Neiden 1914

Bayla Schuchman, born in Gorodish, Russia, emigrated to the U.S. in 1909. By 1914 when this photo was taken her name was Bertha and she was Americanized enough to enter her quilt in the Nebraska State Fair. Her wool patchwork seems to have more in common with the European tradition of tailor's patchwork or intarsia patchwork than the American quilts of her era.

Read more about Bertha Neiden and her quilt:

And read more about wool intarsia quilts here at this post I did a few year ago:

Quilt dated 1880 by an unknown maker in classic American applique style.

One does not find this style of bedding in traditional European cultures.

Quilt historians have looked at quilts and immigrants from many angles. The consensus is that the typical American patchwork quilt derived from a few sources, particularly the tradition of patchwork in India and its trading partners Holland and Britain, combined with a widespread European/Asian tradition of quilted bedding.

"Armenians make quilts Alexandropol,"

probably early 20th century, photo from the Library of Congress

Japanese quilted bedding about 1930

from the Library of Congress.

People all over the world have slept under and on quilted and tied bedding.

American quilts are distinctive in their combination of the two techniques, so distinctive that we can view the acquisition of the techniques and designs as a sign of American acculturation.

European immigrants from the Pennsylvania Germans of the 1600s to the Ashkenazi Jews at the turn of the last century did not bring the patchwork quilt tradition with them.

In the early-19th century the Pennsylvania Germans adapted the bedding of their "English" neighbors to their traditional design sense. It is probably this combination of German folk arts and British bedding format that had the most significant impact on the traditional American quilt.

Unfinished top by Mary Jane Lewis Scruggs

Collection of the Kansas Museum of History

We can see much Germanic design influence in the flat, stylized flowers, red and green colors and mirror-image symmetries in Scrugg's top, evidence of the Pennsylvania-German impact in the American quilt. It is also evidence of this particular African-American quiltmaker's American culture. She was born right after the Civil War to former slaves.

Read more about her quilt top here:

Embroidered quilt, ca 1900, in the collection

of the Jewish Museum

The Museum's caption:

Quilt. Russia and United States, c. 1899 Velvet: embroidered with wool, silk, and metallic thread; glass beads 81 1/2 x 65 in. (207 x 165.1 cm) The Jewish Museum, New York Purchase: Judaica Acquisitions Fund

Cross-stitched embroidery detail showing

European dress and dance

Detail showing cross-stitched rooster

and seam-covered patchwork on the patchwork triangles.

Looking closer at the embroidery I realized that much of it is cross-stitched pictorial work, not typical of the American crazy quilt, which usually features irregular pieces, outlined pictures,satin stitches and seam-covering, linear stitches.

An American crazy quilt

Perhaps the cross-stitch embroidery was done in Russia and the pieces assembled into patchwork in the U.S., a rather unusual example of Americanization in a single quilt.

See another quilt in the Jewish Museum's collection here:

Very interesting read and history about the Jewish culture and quilting, along with other religions. It makes me wonder about religious groups in New England and how that influenced quilts in our area.

ReplyDeleteDebbie

What a fascinating post. As someone who grew up in 1950's- 1960's Kansas, I would observe that only a tiny percentage of the population was Jewish then and probably even fewer before the millions of Eastern Europeans came to America between 1892-1924.

ReplyDeleteSecondly, I'm studying a German American quiltmaker, Anna Catharine Hummel Markey Garnhart, but I don't know how she learned to make what her group called "fancy quilts", I don't think it was a German tradition, if you aren't counting the Dutch. However, the area around her home of Frederick, MD, settled by a mixture of British and German descent, was heavily into "fancy quilts" by the 1840's -- perhaps an English tradition refined by a non-quilting German decorative arts sensibility. Again in Frederick, there was not much of a Jewish presence before the Civil War so I doubt we can't make any statistical inferences.

So many Jewish immigrants were in the garment trade -- but I suppose that since that was what they did for a living, they wouldn't want to piece and quilt scraps in what little leisure time they had. And, as you point out, their Old World origins (Eastern and Middle Europe) did not have a tradition of patchwork. Thanks for sharing the Forward article and for your explication of it.

ReplyDeleteThank you for the interesting post. I have often wondered why my husbands maternal grandmother never made quilts. She made her living being a seamstress and she did all sorts of other handy work like knitting, embroidery and crocheting but there's no evidence she ever did patch work. She was an Ashkenazi Jew from Romania and as you say there is no quilting tradition from that part of the world. And as Nann mentioned maybe sewing all day did not leave much enrgy or interest for patchwork at night.

ReplyDeleteI have been trying to find civil war crossing jelly roll, but I have not been able to find it. Does anyone know where I can find just one jelly roll

ReplyDeleteYou really know your stuff... Keep up the good work!

ReplyDeletebed skirts

I was looking to see if I could find examples of traditional Jewish patchwork patterns, and came across this post! I'm sad there isn't much in that category, but this was a great read and I appreciate it greatly. I'm a potter and I've been looking for quilt patterns to paint on my pottery. When I can, I like to incorporate Judaism into my work, which adds more personal significance and helps me avoid appropriating designs. I don't want to be claiming designs that have meaning and importance to a culture that I don't know about/isn't mine! Thank you for all the great info

ReplyDelete