Let's say it's 1890 and you want to make one of these popular rose quilts. You'll need some Turkey red, something for contrast like a pink, yellow or orange. And of course a lot of green for all those leaves and stems and coxcombs.

There'd be plenty of solid green fabrics out there. In 1890 you had a choice of the old-fashioned natural dyes (vegetable & mineral) or the experimental synthetic greens.

You are looking for a nice grass green, the color of nature.

The color of Kansas in June

So many greens to pick from in 1890....What could go wrong?

Despite all that green in nature dyers and chemists had no reliable vegetable or mineral dyes to create what you are looking for. They could color cotton blue; they could color cotton yellow in a single step---but green was problematic. They solved that problem centuries ago by learning to dye fabric blue over yellow (or vice versa).

Blue plus yellow makes green.

But overdyeing is twice as expensive as a single dye so chemists were always looking for the elusive "Single-Step Green." At the end-of-the 19th century they had many patents.

Date-inscribed 1891

Mary Elizabeth Davis

Plenty could go wrong with the new single-step green formulas. They just weren't color fast and could fade from washing, light or just change over time.

From the Western Pennsylvania project & the Quilt Index

Fading to a khaki color, a tan or a gray.

Or a dull green.

At least this fading was consistent

and a dull green and Turkey red applique is still a delight.

Worst case scenario.

Not a delight.

Sticking with the natural dyes did not mean colorfast. You had two colors that could fade in different ways. The most reliable green might be produced with an indigo blue and a chrome yellow.

Tennessee quilt from a Jeffery S. Evans auction

The dyer might start with the age old vegetable dye indigo. This quiltmaker may have used an indigo blue for her leaves & stems. Or it might be the alternative reliable blue---Prussian blue, a mineral dye.

Some applique artists decided that blue was the perfect shade for the leaves and stems.

Likely meant to be blue. With its pink solid

it may be a 20th-century version.

But most wanted green as did Matilda Whistler.

National Museum of American History

Matilda Whistler (1817-1898) Virginia

Indigo blue plus chrome yellow produced a good green. The only problem (and it was a big one) is that chrome yellow is discharged by acid solutions.

Chrome yellow print with differential fading, probably

due to an acid solution. People are always throwing acids in the laundry,

or dribbling it on the quilt or using lemon juice for a bleach.

Leaf in which the yellow (probably chrome yellow) has

been discharged somehow, leaving blue where it was once

green. We see this on a large scale too.

The maker of this well-used and well-washed quilt may have chosen blue for her leaves but in theory this is what would happen if most of the yellow in an overdyed green was cleared out by an acid. You'd be left with a blue, maybe with a tinge of yellow to it.

The owner of this mid-19th-century sampler told the Michigan

project that all the leaves were green before she washed it.

Another over-dye combination was indigo blue plus an unreliable natural yellow dye. There were plenty of fugitive yellows developed and discarded over the years.

The most common 19th-century combination of natural dyes seems to be the mineral dye Prussian blue plus chrome yellow.

James Collection, International Quilt Museum,

1997.007.0570, Dated 1853

Prussian blue was probably used more than indigo because it was cheaper to produce. The two combined for a work-horse green.

Until you washed the quilt.

UPDATE: Loretta Alterkind says my chart is wrong, wrong, wrong.

Two things going on here---chemistry and directionality. Loretta better at both:

Quilts get washed in laundry solutions that range from alkali to acid (detergents are alkali, additives often acid.) Chrome yellow is discharged out by acids. Prussian blue is discharged by alkali. Detergents from lye soap to Tide are alkali. It's their nature. They wouldn't get clothes clean if they weren't.

Unless your laundry mix has a neutral pH number you are going

to damage either the Prussian blue or the chrome orange in this quilt.

Most often the blue is going to be affected by the detergents

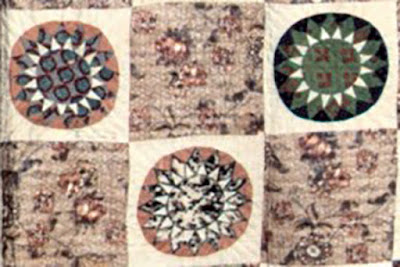

leaving us the common color palette of lime green and red.

And what's not to like about lime green?

The more you use it and wash it and abrade the surfaces the paler the green will get

and the Turkey red will disintegrate.

The maker might have used used two different greens. Here one's fading

to blue, the other just getting paler with age. That brown stain migrating out

from the blue is something Prussian blue often does over time.

Hope you enjoyed the chemistry lesson with the variety of the popular pattern.

Author Chester Himes by Carl Van Vechten, 1946

Himes wrote Cotton Comes to Harlem among

other mysteries.

What do we call that design?

There is no correct name. See a post:

.jpg)