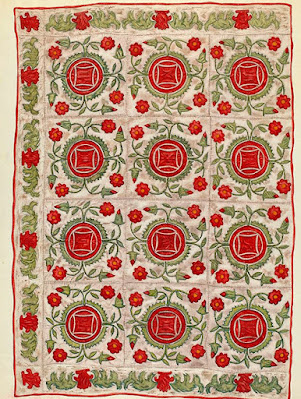

Chintz commemorating the 1851 London Exhibition,

known as the Crystal Palace after the glass building built to house it.

at New York's Exhibition a couple of years later.

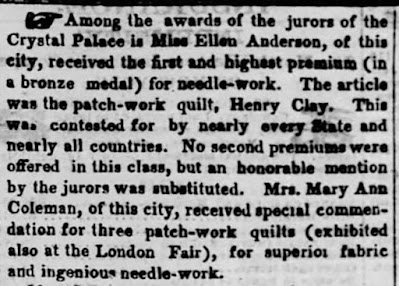

At the top of the list here in one of the textile categories was

Kentuckian Ellen Anderson's "Henry Clay" Patchwork Quilt for

which she won a bronze medal.

Kentucky was proud of Ellen Anderson.

(We'll have to find out about Mary Ann Coleman of Louisville later)

"Is it possible that's made in Kentucky!"

The Kentucky Quilt Project recorded the quilt in the mid 1980s.

Lucretia Hart Clay (1781-1864) and Henry Clay(1777-1852) on

the occasion of their fiftieth anniversary in 1849.

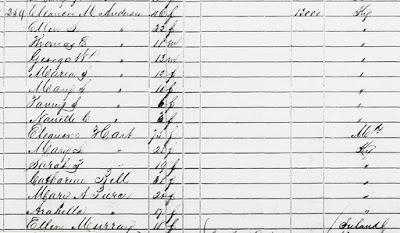

The 1850 census records her living in a household of women. (with two teenage brothers.) Her father George W. Anderson is not listed with the family although he is back with them ten years later.

There is a lot going on here that is difficult to figure out. There are indeed many women in that house: 13 females and two boys and that is just the white people in a slave-holding home.

There is a lot going on here that is difficult to figure out. There are indeed many women in that house: 13 females and two boys and that is just the white people in a slave-holding home.

We can start with Mother Eleanor and her five daughters 3 years old to 25.

We can also look at the 1850 schedule counting the slaves held by people in Jefferson County. Is E.M.

Anderson Ellen's mother? This Kentuckian is listed with two women in their twenties and three children under 7. Two more women to add to the list. In 1821 Eleanor the elder inherited 7 enslaved people from her father: Lewis, Milo, Edward, Edmond, Jack, Sophia and Cornelia, perhaps these people or their parents.

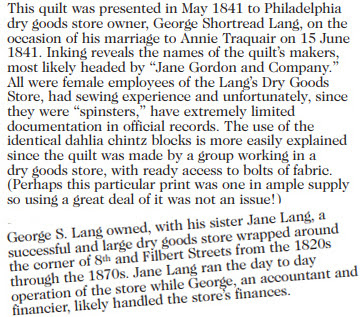

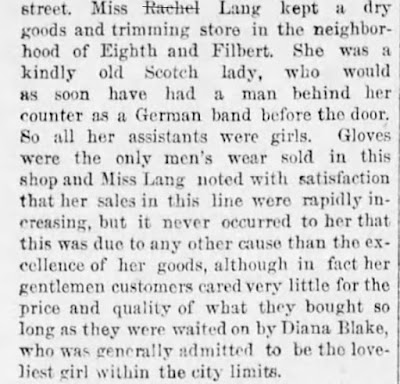

That long list of women includes people who may have worked on this quilt. We have a house of 15 women and a world class quilt. One wonders if its reputation did not increase business for a dressmaker's business, a dry goods shop such as James Anderson's in Louisville or a wholesaler like Thomas Anderson (a relative) who ran an auction house selling dry goods and shoes. My guess at the Anderson family business was confirmed in a biography of Ellen's husband John McCord Harris. He "married Ellen L. Anderson...daughter of George W. Anderson, a Louisville Merchant." George W. Anderson was a partner of Thomas.

Louisville Courier-Journal ad, 1852

Genealogical Narrative of the Hart Family

In 1856 Ellen Anderson married John McCord Harris (1813-1883), a Richmond, Kentucky doctor.

Eastern Kentucky University collection

Their house in Richmond still stands at 515 West Main.

After John's death Ellen married Frank Ditto. She lived till 1902.

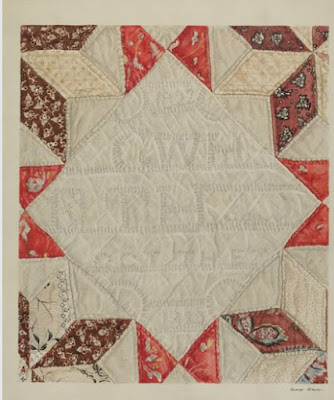

Her famous silk quilt seems to have had several incarnations over the years. It began as a six-pointed star quilt, probably pieced over paper with a tight running stitch.

Many of the stars had faded 130 years later when this

photo was taken.

"The body of the quilt is laid out into stars, each being different in color, and all of them presenting variegations which would be difficult to surpass. The centre of each star is decorated, some by a likeness of the illustrious Kentuckian, and others by an American eagle."

The stars do not appear to be quilted. Each center is a hexagon

with six points framed by shapes of 5-sides each set with white diamonds.

As his great-niece, Ellen must have had access to a good deal of silk printed with portraits of the perennial presidential candidate.

The border is S-o-o-o Kentucky.

"Around the edge of the quilt, about six inches in width is a raised oak wreath, consisting of the leaves and the acorn."

The fringe is brown in this photo from the 1980s---looks like a replacement.

In the 1850s: "a very heavy white silk fringe, fully twelve inches in depth."

A photo of the quilt in 1942 from the Louisville Courier-Journal.

We see the stars and the border. The fringe looks dark.

The center is vague.

"In the center of the quilt is a large monument, surmounted by an urn and immediately under the urn is written ----Session 1850--and below this is [a] Latin motto..." 1853.

The snapshots taken in the 1980s indicate that the quilt was not

quilted. Perhaps the layers were tied or tacked together.

|

| A more recent version is now in the collection of the Henry Clay home Ashland in Lexington. |

It looks like the same star centers and maybe the same stars but the brown silk background is a different fabric and the connecting shapes are no longer diamonds but hexagons. The piece is quilted and bound with a purple border.

This might be all that remains of the wonder of 1850s Kentucky.

Silk can be so fragile. Someone appears to have salvaged stars

and reworked it.

That needlewoman may be Eleanor Garrison Kremer 1892-1986, daughter of Nannette Harris Garrison and perhaps the maker's great-granddaughter. Genealogy in the 1942 newspaper article is a bit confusing.

A long journey across the ocean and back over 170 years.