Tailor with a head of cabbage, 1812

Here's a strange word meaning that illustrates how symbolism becomes lost over time.

We've been posting about jargon and slang and this cartoon illustrates how meaning disappears.

I wondered what cabbage had to do with sewing when I found an 1858 reference to cabbage in regard to "the fashionable dressmaker."

"Cabbage should not be a permitted perquisite when the pattern is unique and cannot be matched."

It wasn't too hard to find out what the heck that sentence meant. (The O.E.D. was on top of it.)

Dressmakers and tailors had two ways of supplying fabric. In one the needleworker provided the wool for a suit or silk for a dress; in the other the customer brought in the fabric.

In either case the establishment kept the leftover pieces. Although the customer might provide the fabric it was a tradition that the seamstress or tailor was entitled to the extra scraps.

From a 1911 dictionary

This was called the cabbage. The term seems related to a French verb cabbaser---to put in a basket. The dressmaker might keep a basket under the worktable for the cabbage.

The Dreamstress blog called our attention to this 1760 painting by Raspal of a French sewing workshop. Under the table: a basket for the cabbage,

which also litters the floor, along with some almost empty spools.

One can imagine how much cabbage was leftover from tightly

fitted bodices like this one in the Victoria & Albert's collection.

But the pieces must have have been quite small.

There were always complaints that the stitchers appropriated more cabbage than was reasonable---

Some of which wound up in their own clothing. The cabbage was also resold to other customers and to wholesalers who then retailed it themselves, as in this 1826 reference to a mantua-maker (dressmaker) who "finds it convenient to sell off her old rags, her cuttings and cabbage, at high prices."

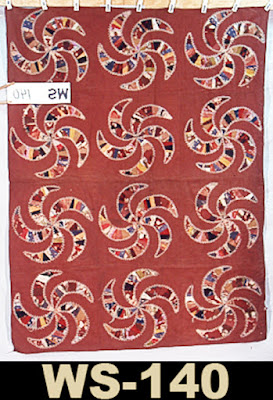

Who would want such small fragments of delaine and challis?

I like it. The cabbage.

"The cabbage" for my container full of scraps too small to save,

which go into a larger box of pieces too small to save.

Another related word is garbage.

I am not kidding.

A 1900 explanation:

"There were few apprentices who did not wear cloth and cassimere vests throughout their entire apprenticeship, that were made of cabbage, and there was no attempt to conceal it, for the privilege was almost universally conceded; and where it was not, in individual cases, the customer was looked upon as 'close fisted,' mean, and penurious. It must be conceded however, that cabbaging was sometimes practiced in such a reckless manner, as to make it little less than downright stealing, and this brought it into disrepute."

See the Dreamstress's post on cabbage:

It's a verb too. Have you ever cabbaged on to something?

Tiny pieces---good for nothing but patchwork?