#3735b

pieced of toile, chintz and linen

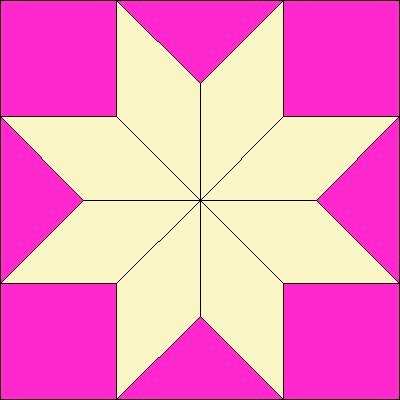

I've been sorting my digital files of stars and found some

pretty complicated patterns, which derive from this basic

star pieced of eight diamonds

#3735 in BlockBase

I thought I'd go back to the basics in the stars based on diamonds.

The star pieced of 8 diamonds is similar to the nine-patch star

#2138 looks much the same but has no Y-seams.

It's often hard to tell if the star is pieced of 8 diamonds

or a nine-patch star. In the detail above this one

seems to be the nine-patch or sawtooth star.

'

G/W/T/ 1795

Made in what is now West Virginia

See more about this quilt at the Quilt Index

Both versions of the variable star go back to

the 18th century. The medallion quilt dated

1795 has the eight-diamond stars in the borders.

As does this medallion dated 1806

in the collection of the Delaware Historical Society.

Clarissa D. Moore 1837

Collection of Old Sturbridge Village

Clarissa Moore (1820-1912), of Eastford, Connecticut, pieced this quilt at the age of 17.

Her variation (#3735b) alternating diamonds in different

shades was quite popular.

She did stenciling in the white spaces behind the stars.

See more about this pieced and stenciled quilt here:

In BlockBase, my digital index of patterns for PC's, I show 5 shading variations: a to e. If you want to look it up by number in BlockBase be sure to type in the a, b, etc.

The popular pattern has many published names although the names were published long after these early examples I am showing here. The oldest names are fairly generic. In 1894 the Ohio Farmer called it Star.

Names from my Encyclopedia of Pieced Quilt Patterns in book format.

About the same time the Ladies Art Company called it Eight Pointed Star

The women who made these early chintz versions

may have had a more poetic name for the design

but we have no records of pattern + name until

the end of the 19th century

Collection of the American Museum in Bath

Once in Susan Parrish's collection

I tend to save pictures of the busy versions with chintz alternate blocks because they really appeal to me, but some early-19th-century examples focused on the patchwork instead of the prints creating a simpler look.

The white plain areas were a good spot for heavy quilting.

A scrappy version mid-19th century?

The pattern remained popular as style changed

after the 1850s

reflecting new fashions in fabric

and the more graphic look of calico-scale fabrics contrasted with white.

#3735d

Perhaps from the first quarter of the 20th century

done in the checks and plaids popular then.

36 star blocks 12" on point = 102" square

Froncie Quinn has done a Hoopla pattern for the Clarissa D. Moore quilt, which would look quite nice in the fabric from my Ladies's Album repro line for Moda.

with the Love's Token Print in Red rose (#8280-20) for the

alternate blocks.

The Hoopla pattern includes the stenciling that Clarissa did too.

http://hooplapatterns.danemcoweb.com/shop/product/clarissa-d-moore-quilt-pattern/